This piece was written after I attended a screening of Lubitsch’s Broken Lullaby at MoMA in August 2014. I never really intended to publish it (I was writing strictly about music at the time). It was more of an academic exercise than anything else. But when Nitrate Diva Nora Fiore was quoted in a recent LA Times article about Universal’s languishing Paramount archive musing on how public availability of Broken Lullaby may alter our understanding of Ernst Lubitsch, I thought it might be time to dig up my own languishing analysis to see how my opinion of my favorite director had been affected by this rare screening. So, here it is.

Poster for the French release with the original French title, literally translated: “The Man I Killed”.

Broken Lullaby (1932)

Director: Ernst Lubitsch

Play: Maurice Rostand

Adaptation: Reginald Berkeley

Screenplay: Samson Raphaelson; Ernest Vajda

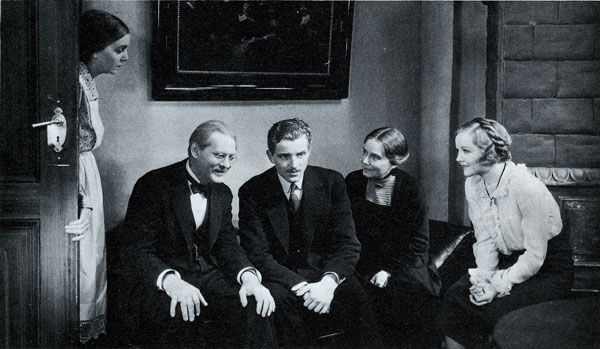

Cast: Lionel Barrymore; Nancy Carroll; Phillips Holmes; Louise Carter; ZaSu Pitts

Broken Lullaby (originally titled The Man I Killed) is a rare dramatic chapter in the Lubitsch Canon, sandwiched between operettas and on the cusp of the effervescent comedic masterpieces that would dominate the director’s post-war reputation. As a drama from the man who made “Garbo laugh”, Broken Lullaby is often overshadowed by the light musicals and justifiably well-regarded comedies. As such, screening are rare and North American DVD copies (legal ones, anyway) are essentially non-existant.

Much of the available commentary regarding Broken Lullaby focuses on the legendary, though largely protean, “Lubitsch Touch” and how it is manifested—if at all—in one of the director’s rare forays into drama. Much is made of the film’s pacifist stance (it was banned in Czechoslovakia for that very reason) and the masterful opening sequence—church aisles flanked by the swords of seated soldiers, a victory parade celebrating shell-shocked vets with cannon fire, viewed through the space where one honoree’s left leg should have been. So much has been said, in fact, that there doesn’t seem to be much point in saying anything else. But something did stand out to me in my sole viewing of this film which I have not seen mentioned elsewhere, but which I feel is crucial to a complete understanding of Broken Lullaby.

Paul Renard (played by an unreasonably handsome Phillips Holmes) is a French soldier haunted by the memory of the man he killed, a former student of the same Paris conservatory, but an enemy in the trenches. When a priest’s absolution and reassurance that he was “only doing his duty” fails to offer him any solace, Paul sets out for Germany to seek the forgiveness of the soldier, Walter Holderlin’s family. It is in the office of Walter’s father, Dr. Holderlin (the inimitable Lionel Barrymore) that Paul first encounters the existential grief that he has personally caused. Before Dr. Holderlin can eject the uninvited Frenchman occupying his office, Walter’s fiancée, Elsa (Nancy Carroll) identifies him as the man who has been leaving flowers at Walter’s grave. The atmosphere shifts drastically and, rather than make his confession of guilt, Paul tells the family desperate for good news, that he and Walter had been close friends in Paris before the war.

Paul is welcomed into the Holderlin’s home, grows closer to Walter’s parents, and forms an attachment to Elsa. All of this leads to some unrest in a town that has lost many sons at the hands of the French soldiers in the latest war, but which culminates in an impassioned speech by Barrymore’s Dr. Holderlin about the futility of war and the dark reality of fathers sending their own sons to their deaths.

It is this speech which is the linchpin of Broken Lullaby‘s “pacifistic theme”. But, poetic and moving as it is, it is something else entirely that saves Broken Lullaby from the curse of trite pacifistic moralizing. After all, of Lubitsch’s preferred vices (and there were many), moralizing was never one.

Throughout the film, Paul is obsessed by his near fetishistic pursuit of the Holderlin’s forgiveness. Without it, life serves little purpose. He sees Walter’s face everywhere, can no longer play his violin, even God’s forgiveness is worthless to him without absolution from the family of the man he killed. And so he treks into socially hostile territory to prostrate himself at the feet of the agrieved and receive his spiritual flogging in pursuit of a clear conscience, until his apparent cowardice forces him into a lie.

As Paul sinks deeper into his deception, he becomes more deeply embedded within the Holderlin family and increasingly mired in guilt. For the Holderlin’s, Paul’s lies are life-giving. By virtue of his deception, Paul Renard is transformed from an implement of suffering into the Voice of God. And in Dr. Holderlin’s social martyrdom on behalf of the rightfully accused, more peace and healing is visited upon the suffering populace than even an array of Arcangels could restore.

Hollywood common sense would dictate that, at some point, Paul Renard’s identity must be made a matter of public record, and it’s entirely possible that, a few years later, the Hayes Code would have necessitated a public confession and either the spiritual execution or schmaltzy pardon of the perpetrator. As it is, Paul Renard’s pre-Code fate takes a different form. When overwhelming guilt at the sight of Walter Holderlin’s bedroom precipitates a full confession to Fraulein Elsa, neither pardon nor exile is forthcoming. Before he can make his anouncement to the rest of the family, his confession is once again preempted, this time by Elsa’s pronouncement that Paul has decided to remain with the family permanently. In so doing, she has taken self-flagellation off the table and meted out his penance, insisting that Paul, who has already killed Walter once, not kill him a second time.

It seems an unfair, almost saccharine resolution. The murderer never pays, never suffers for his crime. But the reality is anything but that. From the first moment we see him, alone in a church, kneeling in desperate prayer, Paul is motivated by the single-minded pursuit of relief for his own unquiet soul. But what, at first, seems a noble pursuit, when set against the grief of the elderly Holderlin’s and the blameless Fraulein Elsa, begins to take on an air of selfishness. By opting to retain him and to keep his identity a secret, Elsa has sentenced him to live happily ever after in Purgatory, being showered in love he knows he can never deserve, responsible for the peace of the people whose suffering he caused. And the longer he fills that role, the further removed he is from his own peace of mind.

As Paul comes to terms with his penance, he is presented with Walter’s violin, which has lain silent since the war. With some trepidation, Paul, whose hands haven’t played a violin since they first picked up a gun, takes the bow and begins to play Schumann’s “Träumerei” (a piece which itself recalls the lost innocence of childhood). The camera, fixed on the Holderlin’s seated in the parlor, tracks the couple’s expression as Elsa, out of shot, joins him on piano.

Great analysis! I had never even heard of this film before! It is so interesting to hear your take on it.

I think that a lot of people, even classic film fans, tend to think only of WWII and the effect it had on people and forget about WWI and how it completely shattered the world. This was the first time there was ever a war like that and people thought it would never happen again. The whole world was reeling from what had happened and the generation of young men that was destroyed. I liked your take on the ending. I wonder too if it was supposed to show that his life was no longer about finding his own comfort, rather he was meant to take comfort in dedicating his life to making up for the son he took away.

That’s certainly a facet of it. There is a certain air of self-sacrifice in the culmination of the relationship between Paul and the Holderlin family. But there is a sort of “eye for an eye”-ness about it. Paul has taken their son. It is now Paul’s responsibility to restore him. When Paul takes up Walter’s violin and begins to play with Walter’s fiancee–two become one–the act is complete. He may as well be playing his own funeral dirge. Paul is dead. Walter now lives. The family is restored.